In the Name Poetry

Musings of Poets on Poetry

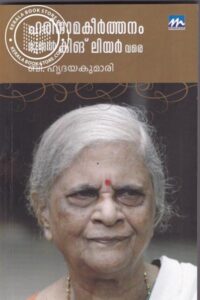

By B Hrdaya Kumari

Professor B. Hrdayakumari is a noted writer, researcher, scholar and critic. She retired from a prestigious teaching career and lives at Thiruvananthapuram. She has many published articles and books to her credit. She is a scholar in Shakespeare Studies and held in high esteem by her students.

Poetry is pure happiness for those who love it, for others it is something that does not matter. To me who loves poetry, a good poem is a total experience like a sunrise or the moon at the edge of the sea. You see it as a whole, you feel it as a whole, and after the first shock of joy, after the first long thrill of discovery you consciously enjoy it bit by bit, line by line, stanza after stanza.

How you enjoy it depends much on your taste, on inbuilt preferences, on the conscious and unconscious levels of the culture you have imbibed all your life. You may linger on the sonorous flow of Milton’s blank verse, or the delicate yet full toned music of Keats or the haunting melody of certain passages in Dylan Thomas. Every genuine poet has his own genuine music, even a standard verse form like the blank verse varying from poet to poet. Not only stanzas, but lines and phrases also have their music, for example, Tennyson’s “there gloom the dark broad seas” or the “the Wave cry, the wind cry, the vast water / of the petrol and the porpoise”, in Eliot. A whole poem can have an orchestral force or be like nature’s own orchestra as in Shelley’s “West Wind”. Whether in English or in other languages, a subtle and sure enjoyment becomes yours when you can relish the music of words, of phrases, of lines, of an entire structure. As the rhythm of a fine piece of sculpture can be felt at its finger tips or the curve of its nose as in its total form. So the Music of a poem too pervades every part.

The Choice of words or making of phrases or the unfolding of a whole line and of line after line is almost magical. Thought and feeling and imagination blend into a single force and it is this force which chooses words and organizes often spontaneously into the whole of a phrase or the whole of a poem. The poet knows the words he uses are older than he and older than the books he has read. They have a life which frightens him, an authority which commands his respect and a beauty which enchants him. When Shakespeare’s Macbeth asks-

“cans’t thou not minister to a mind diseased,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow…?”

Or

Blake sings-

“Tiger, tiger, burning bright

In the forest of the night”

Or Keats complains of “the dull brain” that “perplexes and or retards” or Shakespeare’s Hamlet muses “to be or not to be – that is the question” we can feel the power of right word, the only possible word. But examples isolated like these are no substitute for reading the whole poem and fingering the waft and web of words.

What is all this for? What does the poem say? A poem is a new creation like a flower or a leaf or a human being. It may say many things or nothing; it is what it is. A being and its meaning are not separable. It lives in the reader’s mind communicating may be with his thoughts , may be with his feeling, may be with his sense of history or his sense of his contemporariness with the past or present . But beyond all this it communicates with his sense of himself and of life. If his sense of himself and life is rich, the richer the poem communes with him, grows with him and becomes his ever as he becomes its. It is a mutual give and take, and the process ends only with the reader’s death. The poem lives on.

Hridayakumari (1930 – 8 November 2014) was an Indian writer, educator, scholar, translator, and orator. She wrote primarily in the Malayalam language, and in 1991, was awarded the Kerala Sahitya Academy Award for her book, Kalpanikatha.Hridayakumari taught English at several colleges in the state of Kerala during a forty-year career, eventually retiring as the principal of Government College for Women in Thiruvananthapuram in 1986. She had also taught previously at the University College.She won several awards, including the S Guptan Nair award, the Captain Lakshmi Award, and the Shankaranarayanan Thampi award.

Following her retirement, Hridayakumari gave public lectures on literature, poetry, and philosophy. She also and served on several government committees that dealt with educational reforms in Kerala, and was the chair of a committee that was created by the Kerala State Higher Education Council to reform college credits and semester structures.

She also wrote two books. Kalpanikatha is a study of romanticism in literature, comparing English and Malayalam poets, such as William Wordsworth, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Kumaranasan, Changampuzha Krishna Pillai and Edappally Raghavan Pillai. In 1991, Kalpanikatha won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award. She later published an autobiography, Ormakalile Vasanthakalam, which detailed her experiences as a teacher.

Hridayakumari translated several works between Malayalam and English, including her sister, poet Sugathakumari’s poetry, as well as works by Vallathol Narayana Menon (from Malayalam to English) and by Rabindranath Tagore (from English to Malayalam). Hridayakumari also translated Rathrimazha, a Sahitya-Akademi award-winning novel by Sugathakumari, from Malayalam to English.