Editor’s Choice

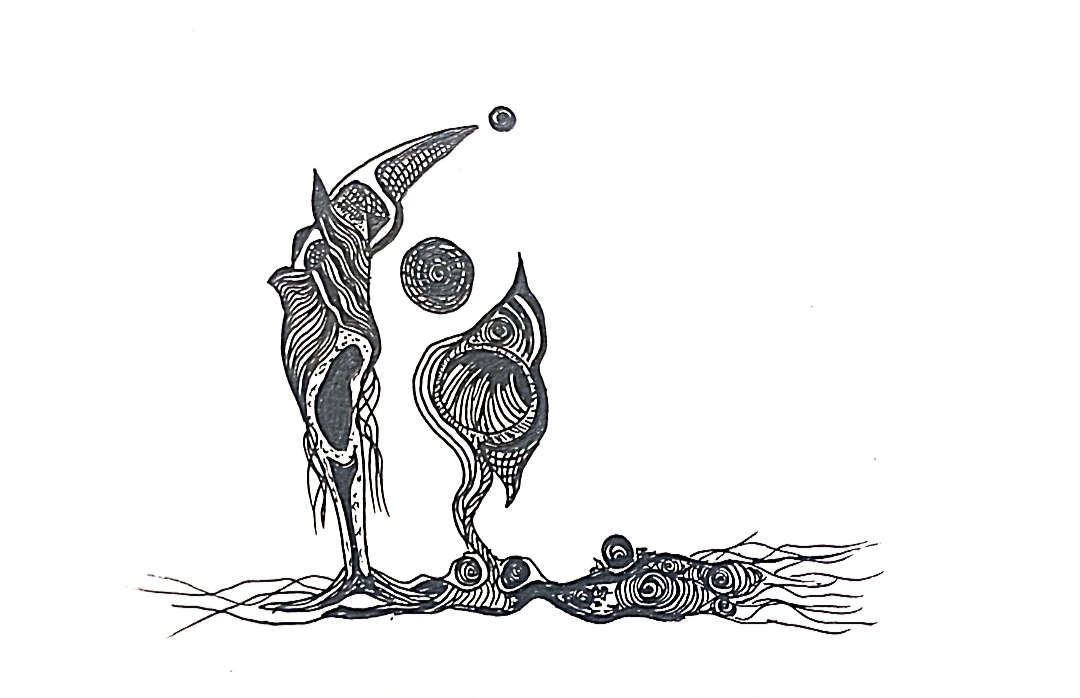

Helge Torvund is one of the most important poets of Norway. I meet him in Norway, a few years ago. His vision and presentation, both are unique. He creates a magic by using his inner imagination and outer world. SERIOUSLY WELL is the long poem, he has written recently and have been translated. I think that this is a treat for poetry lovers, that are why I am presenting whole poem.

RS

SERIOUSLY WELL

by Helge Torvund

There exists an enigmatic art.

A magic alchemy,

an art where one

by means of printing ink

formed like signs

resembling tiny insects,

can make the outer world

and the inner imagination

meet.

By placing

these signs

after each other

in exactly the right way,

selected from an endless amount

of possible ways of connecting them,

you might,

as by a spell,

create a suggestive formula

that evoke feelings

and pictures,

memories, visions of the future

and not the least;

a heartfelt open experience

of being here,

in this moment,

in the reading now.

When you experience this,and become aware

that there exists a great clan

of that kind of magicians out there,

people who has been working tirelessly

creating small mystic books

which are standing hidden

in a gargantuan number of libraries

around the globe,

then your view of the world changes,

and you look around yourself

in joy and wonder.

A great expectation is awakened.

What can you find

in the next thin collection

of poetry?

On the way you will of course

often be disappointed.

You find a leaflet

with a name that creates

expectations,

and like a child you look forward

to get that kind of peace,

where you can find

a quiet place

inside a

not quite awakened day,

where you can sit down

and enjoy these verses.

Then it turns out

that in spite of the beautiful cover

and a well-known name,

just this book is

quite ordinary

and without suppleness.

You put it aside

with a little sigh.

But the glow hasn’t gone out.

Soon you are hunting again.

In the second-hand book shop,

in the book shops threatened

by being closed down.

You are reading in old magazines.

Scrolling through

page after page online.

You are buying unopened books

that have turned yellow.

And still sometimes

you will find a couple of lines,

a little poem,

a little light

shining from a sentence,

which make you lean back,

draw your breath

and feel the strong

old joy;

still the letters of the alphabet

can create gold.

When you have experienced this

you are no longer just one single person

coming from your home village,

from that or that city, from

that or that country.

You belong to another people too.

A population that you can find in all countries.

Like some kind of restless wandering clan

they have left

their mark in all languages.

And the languages have been changed

and transformed

by their trade and work.

Rests and glimmering light

from their work

have entered a larger whole

and have been used

and worn by daily use

from many mouths,

in the writing and thought of many hands.

The glow and the fire

that shine towards you now and then

from the language that the people use,

is the hallmark of the poet.

To sit by the window

inside the great silence

of dawn

and carefully cut open

with a large knife

page after page

in a book full of poetry

from the other side of the world.

From another century.

And feel

while you are reading

some lines,

that your heart beats faster.

To be in contact

with another human being’s

mind, visions and feelings

through letters.

That is magic.

As if a letter

was a magic wand.

Perhaps

the enigmatic in this

is what keeps me

going on.

The feeling that such

an almost impossible thing

really can happen.

That you by using the language

in a certain way,

can establish some kind of

direct contact

between that which is existing

in your inner being and that which exists

in another person’s inner being.

The morning light that

gilds the tips

of the thin naked boughs

of the hardwood forest

now in March,

is changed, gets different,

new, clearer

when you lift

your gaze from a good poem.

But how

can the light out there,

the true

real

sun light

that is kissing the

thinnest tips

of the birch twigs

where the buds

stand waiting,

these buds

that give the whole

hillside

of hardwood trees

a tender

violet tinge

now in March,

how could this

change by the act

of someone sitting inside

reading

a poem?

Is it possible,

is this experience,

that what we see

inside us,

just

an illusion?

I walk the same

road day after day,

but one day

I am so light and cheerful

perhaps I have just

meditated

and my senses are washed

and clean and take in the trees,

the houses and the asphalt paving

and give them this

very special

aura of

this being now

this is real,

that this is unbelievable

clearly existing –

and then

on another day

I am gloomy

heavy

brooding

and the trees, the road

houses

stand out with

another heaviness

maybe irritating

ugly, dirty, glaring.

Who am I

that can change

the world in this way?

Or is there

really

a darkness

out there?

Does there really exist

a diabolic heaviness

that can slowly steal upon

the mind and

the landscape like a dark cloud

and suddenly

chill it all down

make us stiffen

and close ourselves?

And does there then

in the same way exist

a light

a flame

a living glow

that makes us

warm and open?

Is it true that we

are not alone?

That we live

in a connected whole

where we can

open our hearts

and be filled by

peace, confidence,

by light?

Is it

so

that you

by doing that,

by saying no

or yes

can be filled

by another

seriousness,

that you can

awake

and become

even more awake

than awake?

Is it so

that there might come

a more vivid

and connected

life into our life?

Can you

instead of

grieving the awful

deeds you have done,

or shuddering

dread the horror

that may come,

enjoy the fact

that you are

seriously well?

*

When I was a teenager

I always went for a walk

in the bird park.

In a fixed route.

Passed the house of a girl

I once was in love with,

up the hills,

through the clusters of houses,

and in

the enormous gate of wrought iron

to the park.

The gate that

always slammed closed

with a

BANG

a long time after

you had passed

through it.

The doctor had said

that I

had to

go for a walk.

I was dizzy

and anaemic.

Was sitting inside reading

and listening to music.

And I didn’t thrive

at school.

No.

Me neither.

Got pain in my stomach

was giddy and unwell.

The doctor said to the poet,

go for a walk,

and take a spoonful of laxative

every day.

And I did walk.

It became a habit.

I always walked to the bird park,

watched the peacocks,

ducks,

swans.

One evening

something happened.

I was walking

somewhat in my own world.

Pondering on this

that we cannot know

how long we will live.

Someone had just died.

Someone my own age.

And it made an impression.

My namesake even.

It all came strikingly close.

It could have been me.

And then,

there

in the middle of the road,

in the evening light

I suddenly became

completely aware of

the fact

that Death always walks by my side.

I stretched out my hand.

I said: OK; so there you are then.

I might as well shake hands with you,

and accept that you are here.

In this way I included Death in my life.

Death is always walking by my side.

And I have known it all along since then.

I know.

That he’s there.

Perhaps he knows that I am here?

Anyway, I have learned

to live with him.

Still I can sit

in my meditation chair

by the window.

With the view

over the plains

where the morning light

is shivering

and in the distance

the stone bridge

where I so often

have been standing,

and one morning

I feel that I get filled by

the thought of my extinction,

that I will disappear.

The heavy melancholia

I can get

by the thought

of how it all

will continue

without me,

the birds, the morning sun,

and above all:

My children.

My wife.

It is really

unbearable.

But I bear it.

I sit in it.

I allow the sting of it

to fill me.

I sit there

and am

in this experience.

I bear the unbearable,

and then –

little by little

it passes.

Then I am back

by the view,

the morning sun, the birds.

And I feel better.

I am more peaceful.

Even this I can take.

To be completely alive

together with death.

And it feels

completely different

like a comfort in this

that it will go on

without me,

that I don’t have to

bear all this.

I love this light

that was here

the first time

I opened my eyes.

The light

embracing the body

in the pram.

The light

breathing

on the

dark velvet

butterfly wings,

the light

that makes the walls

of the bluebell shine

like thin paper

towards a light bulb.

The light

that opens

the room of the river

lucent

like glass

and shows us

the stones on the bottom;

softened by rolling

in water

glittering from the work

of the time’s polishing machine.

The light over

her lips

this evening

by the bridge,

when I saw

her face

enlightened

from something

inside her.

Did it come up

from the river

and settle

in our bodies?

Did it come

with the soft

misty morning light

and mix with

our glances and

our breath?

Where do you end

and where does

the landscape begin?

Who is this woman

who has been created

by the light

from the bird song?

How is it possible

to open the day

and see the lambs

run

in light soft play

in the middle of

their grass life?

I see the stone light,

wind light,

light in the boughs

and in the song of air –

and I know

my place.

One can think

with light.

One can think

with water.

This soft mist

that embraces the river

and the trees.

All is water.

All is soft movements

in the low light.

A deity of water

that is in everything.

A whizz of the river

and of another day.

An almost inaudible

whistling in the trees.

Round forms

rising and falling

light as white sighs.

The hillside,

the foliage,

the dancing movement

of mist

and we

dancing along.

Everything is here.

All is played with

by the light.

And now and then

I am gliding

out of

myself.

Trembling in the dew.

Dancing in the fog.

*

You are sleeping in a rainbow

beside

a comb of bone.

The day will arrive and lift

our faces to the surface

as the first stones

that are visible

when the water

is getting lower

and the little trembling

before we wake up

and unwrap the first

thought of this day

from its thin paper

of light.

*

I woke up in the middle of the night

and noticed at once

that something,

one thing or another,

was different,

strange, remarkable,

worth noticing.

But I couldn’t make out

what it was.

I slipped out

on the floor

grabbed my bundle

of clothes

and went into the living room.

My wife and the youngest girl

were asleep as

I closed the sleeping room door

behind me.

Outside I saw a full moon and snow.

A landscape

with snow shadow blue colours

and luminescent snow.

I felt something calling for me,

there was something there

that wanted me

to come out.

So I went.

Moonlight over the snow!

Half past three in the night

and I stepped

over the creaking snow

down towards the quay.

Does the fact that you get up

at an unusual hour

change the world outside?

Or was I already in a

peculiar state of mind

that caused me to wake up

in this unchristian time ?

The moonlight is distorting

the landscape

and showing us another side of it.

You recognize it,

but still it is different,

strange, peculiar, odd,

remarkable.

Sinister,

but beautiful too.

Changed. Deformed.

Was that garage usually

placed that close to the road?

Has this lawn always

been this large and strangely illuminated?

Is there something attractive

about the creepy?

The blue, cold.

The air feels thinner

in the luminous frost

and when you draw your breath

it is like you

draw a cold spirit

into your body.

And then you let

it out again

like a ghost of frosty smoke.

Down on the quay

someone had left a stand.

In the middle of the concrete area

I noticed a stand like the one you can put empty

sacks on when you are going to fill them

with one thing or another.

I didn’t pay much attention to it

until I noticed

a movement there.

Something was moving.

And suddenly I saw what it was:

A large narrow head of a bird was rising

from the stand and looking at me.

The whole stand turned out to be a heron

standing there

on the ice cold concrete,

sleeping.

I went a bit closer,

stopped for a while.

I saw an ancient gaze

staring at me over

the long narrow beak.

There was a great wisdom

in that eye.

I moved even closer.

It did not fly away?

No.

How

strange.

Suddenly it laid down

on the concrete.

And the eyes

became begging, helpless.

I walked away from it to let

the large grey bird be in peace.

I walked around the harbor

and up to some of my view places.

Inhaling the bluish nightlight.

Freezing a little almost at once

when I didn’t move.

Then I walked homewards

and had to have a look

at the heron again.

But now it was dead.

It lay there flat and stiff on the icy concrete.

I watched it,

and I imagined

how those mighty wings

had let it fleet

through the air

over the rocks

around the harbor

with its long legs

stretched out behind it.

How it had been standing

immovable in the water waiting.

Immovable in the rain,

just like a Japanese

artist has caught a heron

in a woodcut.

And then!

Suddenly it snaps a fish.

A life in patience, in air and water.

And now, the end,

silence, cold.

*

I was freezing.

And suddenly

while walking

back home,

I was thinking

of The Restless One.

He who all the time

was walking around in the park,

picking up

dead birds

and paper,

sticks.

He who was living by himself

in the little house

close to the large park

with the old tall oaks.

The park that was placed

in front of the hospital,

and on the other side

close to the cemetery

by the old stone church.

He used to pick up

withered leaves there,

yes,

now and then

a dead bird

or a dead animal

even,

from the large lawn

in the park.

Not many of those

though.

Mostly leaves

and sticks

And stones.

Many sticks and twigs.

Sometimes we could see

him bowing down

picking up something,

but we didn’t see

that there was anything there.

It looked like

he was picking up

invisible things.

He wandered around

mumbling

and restless.

Walking from here to there.

Paused,

talking into thin air,

looking at the ground,

As if he

never was at ease.

He bought things too.

All kinds

of little things

and remedies in the shop.

The old shop

where there was

a little bell

tingling

when you opened the door.

The one shop being

close to the hospital

on the opposite side

of the church.

I don’t think the man

behind the counter

was very pleased

when he arrived.

Perhaps he was afraid?

Well, not that he was afraid

of The Restless One,

that he should do him any harm,

he was a thin

grey haired man,

The Restless One,

in a grey overcoat that was

a little too big for him.

A timeless garment.

Such an overcoat

you can imagine

hanging on

a stand

in a dusty

derelict shop

in a village

where almost everyone

has moved away.

A coat

that almost

from a little distance

could make

him look like

a sleeping

heron.

The shopkeeper

was much bigger

and more athletic

than The Restless One.

Tall and

almost fat.

Bald, but always

wearing a little cap

that looked like a kipa.

I noticed that,

because it was rather unusual,

nobody around here

wear that kind

of cap.

No.

I think the shopkeeper

was afraid

that people should believe

that he did palm things off on

The Restless One.

That he was somehow

making the most of the old

restless man by making him

buy all those things.

He seemed embarrassed

when he came.

He bought

all kinds of useless things, too.

But I guess the shopkeeper

just couldn’t make himself

say no to him, either.

The Restless One seemed a bit

embarrassed himself.

A little uncomfortable.

Like a young

man going to

buy condoms

from a mature woman.

Nobody knows what he

wanted those

things for.

He bought sticks.

Chopsticks.

Wooden plant sticks.

Knitting needles.

And spools of thread.

With sewing thread,

and thicker threads.

Sometimes a rope.

He put it all

into his old

brown handbag.

He brought them home.

The little house

in the end of the park

had to be filled up

with such things.

But we never saw what he did

with the other things,

those that he picked up

in the park.

We saw him

gathering them,

putting them

in small heaps

in the gravel

on the footpath.

Then he tried through

executing some rituals,

some strange kind of alchemy,

to lead these dead things

that he had

gathered there

in the evening light

between the tall trees

in the park,

to bring them over

to another form

of life.

He moved his hands

over them

while he

all the time

mumbled

inaudible formulas.

His mouth moving

constantly.

He could keep on

with these rigmaroles

for hours,

alone.

Sometimes

my uncle was

with him.

He was a doctor

at the hospital.

Yes, he is

dead now.

But back then he was young.

A successful doctor.

A well-known psychiatrist.

He never told

us anything,

but after

The Restless One

was dead,

he once told

something

to my father

who passed it on to me.

My uncle had said

that he didn’t know

how to help The Restless One.

That he was quite

uncomfortable

sitting like that.

He was sitting there on the bench

by the green

while The Restless One

was walking nervously

and manic

around

picking up new things.

My uncle tried to

carry on a conversation.

For an hour

every week

he was sitting there.

It was the scheduled hour

The Restless One

was supposed to have

in my uncle’s office.

But The Restless One

was so anxious and fidgety

that he couldn’t stay

in my uncle’s office.

After being in the park

for some times,

The Restless One

started to show his

despair more

and more openly.

My uncle was always

very calm.

Even though

it was uncomfortable

for him too, this.

But The Restless One

become more and more

desperate

because he didn’t succeed

to transform the dead things

into living creatures,

because he wasn’t able

to give them life.

But then, one autumn day

he quite unexpectedly sat down

on the park bench

beside my uncle.

They were completely silent.

both of them.

The Restless One was sitting there

looking out over the lawn.

It was full of withered

maple leaves

oak leaves

and sticks that the storms

had blown down.

Uncle was secretly watching

The Restless One.

He said nothing,

the mumbling had stopped.

And uncle saw

in the soft and golden light

that the face of The Restless one

was filled with tenderness

filled with naked sorrow.

With tears in his eyes

he said reconciled:

“I can for instance not

transform a leaf

to a sheep.”

“No”, said uncle,

“that is true.

And that’s the way it is

with humans too.

They live

and they die.”

The Restless one nodded.

“Yes.”

*

When I was twelve years old,

I came out on the stairs

in front of our house

and saw the yellow outhouse

and the blooming elder.

The smell from the rabbit cages

and from the dwarf chickens

was underneath all other smells in the air,

and on the clotheslines

white linen were flapping.

My hand can still remember

how it was

to touch the cold cross-bar

on my bike,

and I can feel

the light steps

along the yard

in my body

before I got on to the seat of my bike.

It was a wind life.

A life with the scent

of resin

from friendly pine trees

where one had been swinging

the childhood away

softly through

afternoons that was just

being good to you.

When I was twelve year old

the world was twelve years old

and the heaps of sand

was high and yellow

and the sun gave

the whole landscape

an energy

that made it grow

towards heaven.

*

To step out

on the stairs,

or to come

in to the doctor’s office,

to stand and take in the day

not knowing what

to do with it,

or sit there

in front of the doctor

who is saying

a few words

that changes

your whole life,

such moments

make me think

about a person who

is about to

create by improvisation

a piece of music,

I mean,

just imagine:

He is coming on stage.

And there it is only him

and the grand piano.

The grand piano over there.

Black

and polished, shining.

And himself,

with his lived life,

his sorrow

and his joy.

Sleeping

under a grand piano

as a child.

The concerts

with great musicians

around half of the world

as a grown up.

And now.

Sold out house.

Filled with people

full of expectations.

Whatever you have done

before,

it is now

only now

that counts.

To walk over to

the grand piano

with your fingers.

You know that this

instrument

isn’t the one you prefer.

In fact

you were thinking of

cancelling

the concert.

You have not

eaten much, because

you didn’t like what

they served at the

Italian restaurant.

And you have not slept well.

You have been driving

from Zurich

to Cologne.

You are tired,

it is

close to midnight.

You

most of all

would like to drop this.

But then you feel

the expectation.

The people.

Listening, waiting.

And so you sit down

in front of the keyboard.

Now.

This is the moment.

When your fingertips

meet the keys

nobody knows what

is going to happen.

Nobody knows

what this will lead to.

Perhaps

the hands know?

You said that,

afterwards,

in an interview.

Or did you say;

The hands know?

Who knows?

Anyway, this is

the moment of truth.

You have no sheet music.

You have no

musicians to help you out.

You’ve got yourself

and all you have done before,

rehearsals,

listening,

hands,

and you have your audience.

And the audience

is yourself,

multiplied

with thousand ears.

The listening expectation.

And each and every one

is not you,

but themselves,

their own unique listening.

Their unique expectation,

Halting now just where

they have come

in their wandering.

All these different lives

listening now:

How vulnerable

this moment is!

You put your fingers down

and the world is black and white.

And from the black and white

you start to create

all kinds of colors.

All the sounds

all the tone colors

from green to blue

and from grey to

yellow.

You improvise

a life.

You follow

your fingers.

You make the piano

imitate a phrase played

by the bells in the lobby

to tell the audience

that it is time to go in to

the theatre.

Someone laughs discreetly.

They notice what you’re doing.

The grand piano

is an echo of the moment

that just passed.

The grand piano becomes

an enormous container

filled to the brim

with lived life.

Vibrating

dancing

catching

living

sensing

life.

You

and those

down there.

No!

You

and the grand piano.

Just you

and the piano now.

Every movement

you make,

every tune

following the tune that just

faded,

recreates

the room.

You establish

the atmosphere

that embraces

everyone in the audience.

You are

a magician

who let your fingers run

over black and white

and while you

build a house

of rhythm,

put together of

a wall of bass

and tempo

and opening

treble,

windows

of clear glass,

you conjure all this up

through this troll tuned

vibrating

creature,

and you moan.

You groan

under the tremendous

power.

You walk up

these stairs

from darkness

to light,

uncertain of

where you are

or of where you are going,

and it is all

open.

Or is it

closed?

Locked up in

luck?

In mere chance?

No,

neither.

Open or closed

are only words now.

And you exists

in a wordless

music.

Vulnerable and swinging,

fragile and

exposed

and near.

Living,

breathing,

for heaven’s sake,

you breath out

the groaning rhythm,

you breath in

the music.

The room is moving.

The whole room

is changing

and leaning a bit over

in minor.

Light

is growing.

You are growing.

The audience are listening.

Nodding.

Rhythmically.

They are happy.

You are taking them

upwards

outwards

deep.

And they follow you.

*

But

one afternoon

in December

my GP sits down

after having examined me.

He looks at me

and says

in a serious voice:

“You have got a lump.”

I remain calm in my seat,

but inside

everything stops.

As from a distance

I hear him say

“I am going to make a call

to the hospital

and book all the necessary

examinations for you.

Do you want to stay in here,

or do you want to go out

to the corridor and wait

for a while?

It’s your decision!”

I go out to the corridor,

sit down.

But I am not able to sit.

I am not able to sit quietly!

Must move.

Walk.

Back and forth in the corridor.

I am alone there.

But I think

I just have to

calm down.

Now.

I sit down.

An anxious restlessness

seizes my body.

A physical

shaking

alarm.

Furious

feelings

storm through me.

My God!

What is happening?

Must move.

No, now I’ll have to

collect myself.

What is happening here?

First and foremost

the unbearable thought:

Soon I’ll have to go home

and tell her this.

And tell the children.

Well, I don’t really know anything yet.

It’s all unclear, uncertain.

Suddenly.

How long?

To tell this

to the children

and to her?

*

The doctor comes to the door

and says

that I might come in again.

*The anxiety stays with me

while the GP explains

what will happen,

and gives me the different times

for appointments

I now have got at the hospital.

The anxiety stays with me

when I say goodbye to him,

walk through the

empty waiting room

and down the road

towards the railway station.

The anxiety is so strong

that I am not even able

to collect my thoughts

in order to formulate

the burning question:

How will they take this?

What am I going to say?

The anxiety stays with me.

It is tearing me apart

as I am standing

on the platform

and have some minutes

before my train arrives.

*

But then!

There!

In the December afternoon sun,

something happens.

I turn towards it.

I make contact with it.

And suddenly I am able to say,

OK,

now it’s like this.

Like this it is.

And here I stand.

And the anxiety goes away.

And I am

peaceful.

It is now.

It is singing in metal.

Bells.

Strings.

We can feel it vibrating.

We recognize it.

It is our

sound.

It is us.

It is clinging.

Ringing.Rhythmically beating

and alive.

We are gone.

We are born.

We are passing in and out of this.

Everything is rhythm.

All is changing

in sound

and pace.

I board

the train.

You are sounding.

I am sounding.

You come.

It is the ringing of the light.

This

is the deep sounds of bass in us.

And a melody of light.

A dance.

We’ll see.

It proceeds tentatively.

I am without any clues.

Without guiding principles.

Leaning forward.

Put words on it.

Get something in place.

Word for word.

Letter for letter.

My thought was:

This will be as it will be.

This is like it is.

An enormous confidence rose in me

and filled me.

Not a confidence in me becoming well,

or that something special

was going to happen at all.

I had no clues except this one:

A feeling that told me

that when it is darkening around the heart,

and the time is shrinking,

you have to embrace the fear

and give yourself over

to an insane confidence.A confidence that told me

that the very best thing to do for me

was to be where I am,

be alive

in that which is.

The anxiety really did disappear.

I could board the train.

They would have to be like they are.

And I was like I was.

Everything is like it is.

And so it was.

So it was to be.

*From the train

I saw

a heron

flying

with heavy

movements of its wings

outwards over

the huge illuminated

expanse

of the ocean.

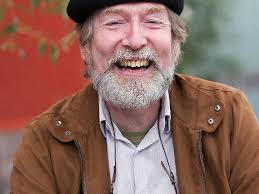

Helge Torvund  (born 20 August 1951) is a Norwegian psychologist, poet, essayist, literary critic and children’s writer. He was born in Hå municipality and is brother of sculptor Gunnar Torvund.

(born 20 August 1951) is a Norwegian psychologist, poet, essayist, literary critic and children’s writer. He was born in Hå municipality and is brother of sculptor Gunnar Torvund.

He made his literary debut in 1977 with Hendene i byen. In 1989 he was awarded the Nynorsk Literature Prize for the poetry collection Den monotone triumf. He received the Herman Wildenvey Poetry Award in 2016. From 2015 he has been writing monthly in the newspaper Klassekampen. One of these articles has been translated and published by York Art Gallery as “Carnal Light”.

He was awarded the Dobloug Prize in 2018.