In The Name of Poetry

Get to know Babitha Marina Justin: Poet, Artist, Editor

By Michelle D’costa

Babitha Marina Justin is a writer, artist and academic from Kerala. A Pushcart Prize nominee, 2018, her poems and short stories have appeared in twenty international journals like Eclectica, Esthetic Apostle, The Paragon Press, Fulcrum, The Scriblerus, Trampset, Constellations, etc. She has authored five books which include two collections of poems, Of Fireflies Guns and the Hills (2016) and I Cook my Own Feast (2019). Her other books are Humor: Texts and Contexts (ed. 2015), Of Canons and Trauma (2017, A collection of essays for literature students) and Salt and Pepper and Solverlinings: Celebrating our Grandmothers (ed. with Abhirami Sriram, 2019). She is waiting to debut as a novelist with Sandpaper Memories (2020).

How and when did you get attracted to poetry?

Once, I wrote rhymes on the walls as a five year old. I remember it was in Malayalam and it was a three liner about a coconut falling in the yard. My spellings were all wrong then and I got teased for it as it became a kind of family joke.

Then like any teenager, I wrote poetry when I fell in love. I left poetry for academics. I renewed my interest in poetry at 28, when I was alone in the rolling hills of Tura, Meghalaya. I was lonely, desperate and away from my family, and I chanced upon a Northeastern Poetic community. I got acquainted with the astounding poetry of Robin Ngangom, Mona Zote and Guru Tsering Ladaki and I was home in the hills, with my poetry to bolster me.

Afterwards, there was no looking back.

One Indian poet you love to reread:

Robin Ngangom: There’s much passion and movement in his poetry as he toes the fine-lines between political conflict , desire and longing. Any day, I would love to hold a copy of Desire for Roots in my hands.AK Ramanujan comes a close second.

You’ve been published in many online journals, did it give you the confidence to then publish your own collection?

I didn’t know this joy of getting published online when I published my first collection, Of Fireflies, Guns and the Hills (2015). I used to put up all my poems online for instant gratification. Then I compiled all of them, got them edited thoroughly and published. One day, I came across this App, Submittable and I submitted a poem for Eclectica. I forgot about it, but I was overjoyed to see the acceptance mail. Then I got my poems edited and submitted as many poems on Submittable. In a single year, twenty six poems were published online and in print. A poem was even nominated for the Pushcart prize in 2018. I picked another twenty poems for my collection and came out with my second collection, I Cook my Own Feast (2019).

The best part was the way rejections affected me. My acceptance rate was 5: 1, and every time I got rejected, I reworked my poem and submitted again. Thus, it was a constant process of editing, reworking, submitting, editing again….

Have you explored writing fiction?

Yes, I have published my short stories too online and offline. My Short Fiction, “My Blue Eyed Brown Aunt” made it to the Best of Small Fictions anthology in 2019.

From 2016 onwards, I have been writing my novel, Sandpaper Memories, aka, Maria’s Swamp. Though I finished my novel in six months, I went through excruciating pain and depression. I was crying for weeks together and I went into a medication phase. I felt wasted and lived like a vegetable. My children were appalled at my transformation. Then I understood that recreating and readapting childhood memories don’t heal. Writing did not heal me, but rather messed me up. I had to undergo intense therapeutic sessions to get over the trauma of writing. Now the novel has undergone several changes and transformed through many drafts. Four professionals have edited it, and now it is in the final stage of waiting for the publisher nod. I have a couple of publishers to choose from. But I worked hard on the novel. Even now, prose is a bit more difficult for me to write.

I loved the way you explored our consumption of ‘news’ in your poem ‘I Cook My Own Feast’. How did you get the idea for the poem and why is it the title of your collection?

I work in the middle of chaos. I live in a joint family with two teenage sons who constantly demand my time and attention. It is like the warfront, I need to manage my personal life, my teaching profession, paint everyday and write as well. So usually it is between my work, I write. One day, I charred some exotic spicy chicken in watermelon rind, and I happened to listen to the news on TV about the Afghan blasts. I was in the middle of one of the worst paradoxes of my life, here I am cooking exotic stuff in the comfort conch shell of a home, when the world is falling apart. I realized that poetry is also like that, it is my effort to find a bit of peace just on time before my own world falls apart. I jotted down the poem in the kitchen, while the watermelon stuffed with chicken was getting charred in a heap of burning coal.

Can you tell us why you structured the book into three sections- Birthmark, I Cook My Own Feast and Dateline?

That was the publisher, Dibyajyoti’s decision. The first part is about my personal relationships and me, the second part about my craft of writing and the third part, the Dateline, my perspectives on life.

One of my favourite poems from the collection is ‘Churchgoing’ for the way you explore the narrator’s discomfort with religion.

‘Their razor-edge gaze pinning down my wax wings’

What a line! Religion/Spirituality seems to be a recurrent theme in your poems. Do you see a personal growth/catharsis after writing these poems?

For me religion is personal, and spirituality is my own personal growth, and both are not inclusive of each other. I am irreligious, yet a spiritual person. I grew up as a dyslexic child in a convent school. Understandably, I am deeply critical of institutions like family, religion and education. Sometimes I think, it took a life-time of trauma for me to grow out of these institutions or else be complacent about them.

My parents were Catholic, but not very religious too, but as children I remember my tortuous hours during catechism and Sunday school. From my childhood, I understood that these aren’t the safe, secure and happy places which they pretend to be. I could never ever fit into them. I have always sensed the bristles of hypocrisy emanating from these institutions.

I work in the middle of chaos. I live in a joint family with two teenage sons who constantly demand my time and attention. These lines from your poem ‘Onam’ seems like a summary of your whole book-‘On the green banana leaf of memory, I serve myself a smidgen of each, the sweet, the sour and the bitter.’ Any comments?

Childhood festivities and celebrations are deeply embedded in my memory. My entire collection is about playing with memories: the present and the past. The synaesthetic flavors of my childhood, unfortunately embroil deeply into my present life as well. The sweet, bitter, sour flavors still linger, taking another form as an adult steeped in a capitalistic world. Though, there was a mixture of memories, everything used to be much simpler, then. I never had a perfect childhood, but my memories are much vivid and fresh in my mind.

Did you write poems intending to include it in this collection or is it an amalgamation of poems written at different points?

I wrote these poems at different stages and I put together the published ones and unpublished favorites into this collection. These were written from 2016-19.

I loved your poem ‘An Anthem For Brown’. When were you inspired to write this poem?

Kerala is a land sizzling with brown racism. I had, from my childhood, been at the receiving end of it. I could see people only as brown and I was darker brown. When people called themselves as fair and dark, I was confused. When I was in Delhi, again I faced brown racism at its heights. I had a Spanish friend , who used to joke with me that though she was considered rather plain in Spain, Indians treated her like a beauty queen for her skin colour.

From then onwards, I had been critical of this brown racism, and the way we got a colonial kick whenever we were in denial of our brown skin. This poem is a critique of brown racism and my sarcastic take on it.

Being a night owl, I really enjoyed your poem ‘Snore Catcher’. The way you explore ‘snores’ through the poem is wonderful! Do you think a poet needs to be more observant than a fiction writer for example to catch such moments that could be converted into short poems?

In fact ‘The Snorecatcher’ is about one of those sleepless nights. As I live in a joint family, sometimes I have to keep an account of the family snores and farts and all those private stuff, which at times are disgusting. Poetry is sometimes my way of rolling up my eyes and throwing up my hand in disgust. It is the only space where I have some kind of privacy. I am observant there, one hundred percent honest and absolutely unforgiving.

Though in fiction, ‘Snorecatcher’ could have had its moments of hilarity, I would rather catch a trace of sadness in its poetic form.

I expected more Malayalam words in your poems. Was it a deliberate choice to not include many vernacular words?

In Onam, I have used Malayalam words. But, not elsewhere. In poetry, I think in English. But in my fiction, I have used a lot of Malayalam words with their translations.

There are very few publishers of poetry in India. Can you tell us about your publishing experience with Red River Press?

I love the Red River experience. Dibya is one of those people who are so easy to work with. Moreover, as an editor, he has a sense of poetic divisions and basically, he visualizes your book more effectively than you do. I like that deep sense of aesthetics, that is very important. That is precisely one of the reasons people want to be published with Red River. Their marketing strategies are competent, they have a handful of young and established poets in their fold and in five to ten years time, they will be one of those poetry publishers to be reckoned with.

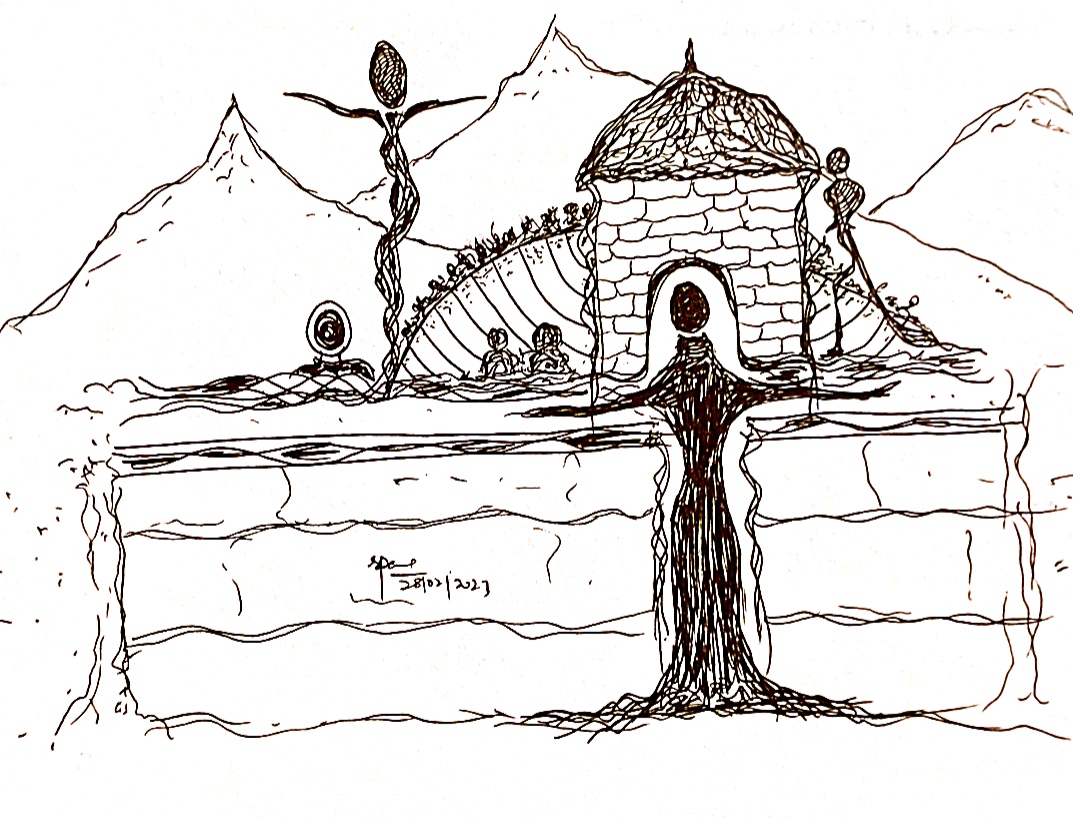

I love the way art and poetry intersect in your book. Did you illustrate the poems only for the collection?

Art is again part of my writing, I keep doodling all the time. Once I write, I want that writing to be complemented by my art, for example, for my upcoming novel, Sandpaper Memories, I have illustrated ten pieces which go along with its plot. It is not incidental, but the story remains deep inside that I give expression both through writing and painting (and at times doodling).

What are your inspirations as an artist and does it stem from the same place as a poet?

I started painting very late in my life; from my childhood onwards, I had been pretty good at sketching. I lived with the burden of so many images in my mind, all I needed to do was, sit back the rest of my life and paint them. I have already conducted a solo and have been part of many group exhibitions. I have also sold away many paintings for charity as well. I just want to write and paint till I die, I have no bigger ambitions beyond that. I think, inside me, both the poetic and artistic sensibilities co exist. They are not inseparable from each other.

I love the Red River experience. Dibya is one of those people who are so easy to work with.

Your range as an artist in commendable. From animate to inanimate objects, you have shown a variety in your collection. Since when are you sketching?

I have been sketching since childhood. I painted most of the inanimate for my friends, which were commissioned. But I am deeply enamored with figures. I have started a series on male nudes. I have finished my first two paintings where my father is Adam and my son, is Jacob. I have to finish a few more to conduct a solo of my male nudes. The trouble is, now lots of my male friends run away from me asking me not to feature them in my paintings. I am only painting the men I know intimately in nude 😀

You have co-edited the anthology ‘Salt & Pepper & Silver Linings’ which focuses on writers’ accounts of their grandmothers. How did the idea for such an anthology come to you?

My editor friend, Abhirami Girija Sriram, had once written a touching tribute to her grandmother on FB. I too had many things to say about my own grandmother. I just asked her if we could jointly edit a book and we sent the concept notes to many writers we knew on FB after doing a thorough research on the NET regarding granddaughters writing about their grandmothers. Many of the writers responded with a resounding yes! And they were so glad to send us their works. Thus, we begin with

Ayyankali’s (the Dalit Reformer in Kerala) great granddaughter’s narrative and we round it off with a Dalit gender activist, Vaikhari, who is firm on writing the silenced women back into history.

How was the experience ‘co-editing’ the anthology? Have you ever tried to ‘co-write’ something? I’m always intrigued about this working of two minds on a project and I wonder how it went for you.

Abhirami is a tough taskmaster at editing. I am good at PR work. I made a list of writers and solicited work from them. Then made a calendar and accordingly I started collecting and putting together work. When the MS was ready, I sighed in relief thinking it is over. But then, the editing began. Abhirami is a meticulous editor, we went through the drafts together, she was in Chennai and I, in Trivandrum, and then I would run to the designer with the corrected draft. By the end of this tedium, two years had passed and what we had at the end was a neat manuscript. So the experience was so rewarding. Abbhirami always thought, this editing together business is going to bury our friendship which started from our MPhil days in JNU. But now it has come to this, a manuscript between us brings us closer.

I have been sketching since childhood.

The anthology has poems by eminent female poets like Annie Zaidi, Tishani Doshi, etc. How did you pick writers for the collection?

They were my FB friends and the contemporary women writers of India. So it was easier to choose them.

I loved your story ‘Mariamma’. Did you write it for the anthology or was it something you had explored before?

‘Mariamma’ is part of the novel, Sandpaper Memories. This short story is part autobiographical and part fictional, as much as my novel is. I have put together tidbits of childhood memory with the plot I formed as part of story telling. In fact, I wrote a more realistic piece for the grandmother collection, but I kept it aside as it was too revealing.

I particularly enjoyed Manjiri Indurkar’s piece ‘My grandmother: the narrator of childhood horror stories’. Was there any editorial intervention in the pieces submitted as you’re a writer yourself?

Not at all. Manjiri wanted the story to be as it is. So we left it as it is.

You teach English as well, how does it influence your writing?

I have become more conscious of language and how it is used after I got into teaching. At one point, we were all made to believe that writing springs out of talent and spontaneity. Now, writing is more of a self-conscious act for me. Editing, a painful and laborious process.

‘Mariamma’ is part of the novel, Sandpaper Memories. This short story is part autobiographical and part fictional, as much as my novel is.

Which poem do you like teaching and interpreting over and over again?

‘Personal Helicon’ by Seamus Heaney